A BRIEF HISTORY OF BEAR MARKETS

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BEAR MARKETS

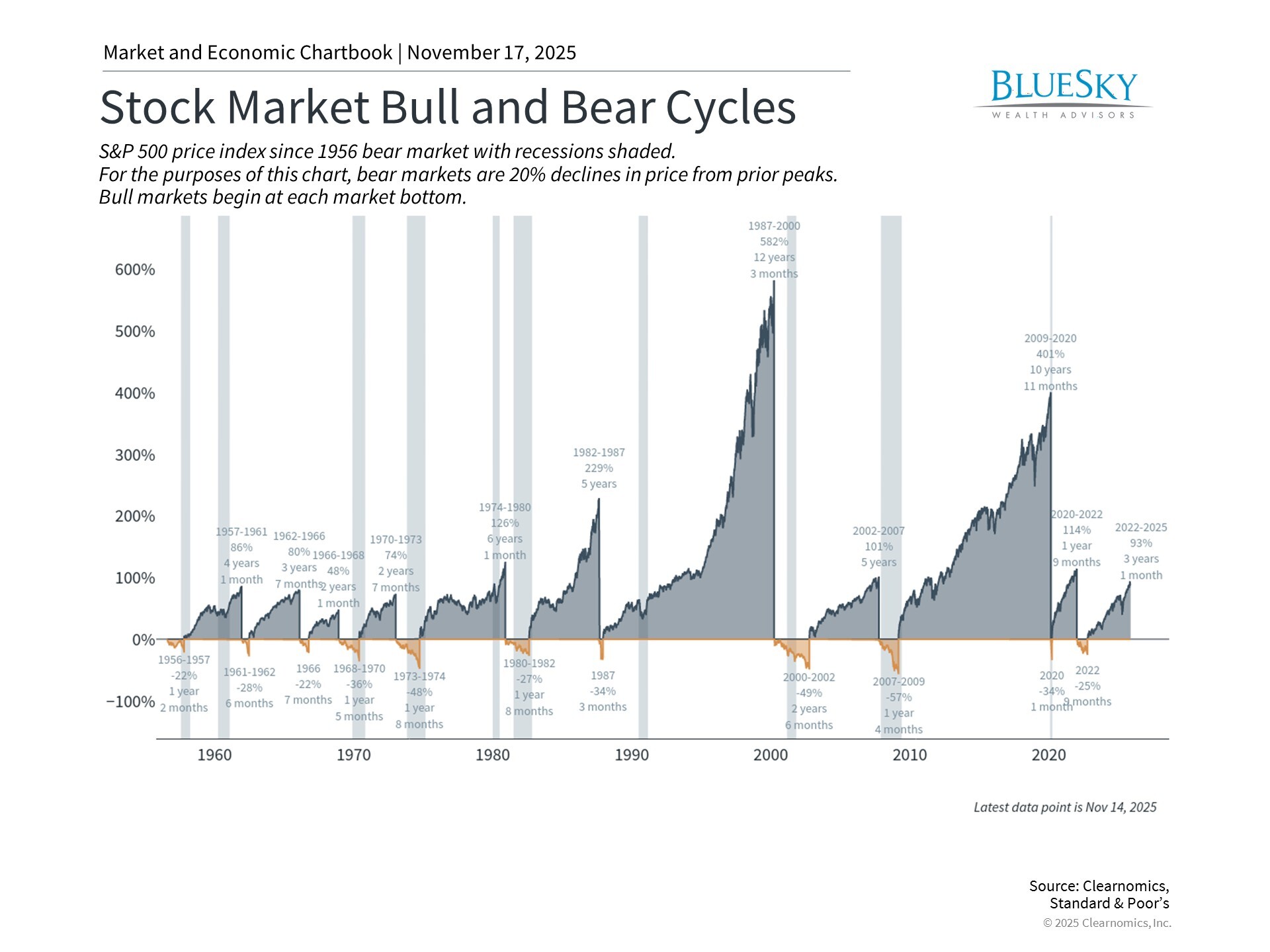

Any discussion of bear markets should begin with an explanation of what they are. Bear markets are generally defined as an extended drop in multiple broad market indices (e.g. S&P, Dow Jones, NASDAQ) of 20 percent or more.

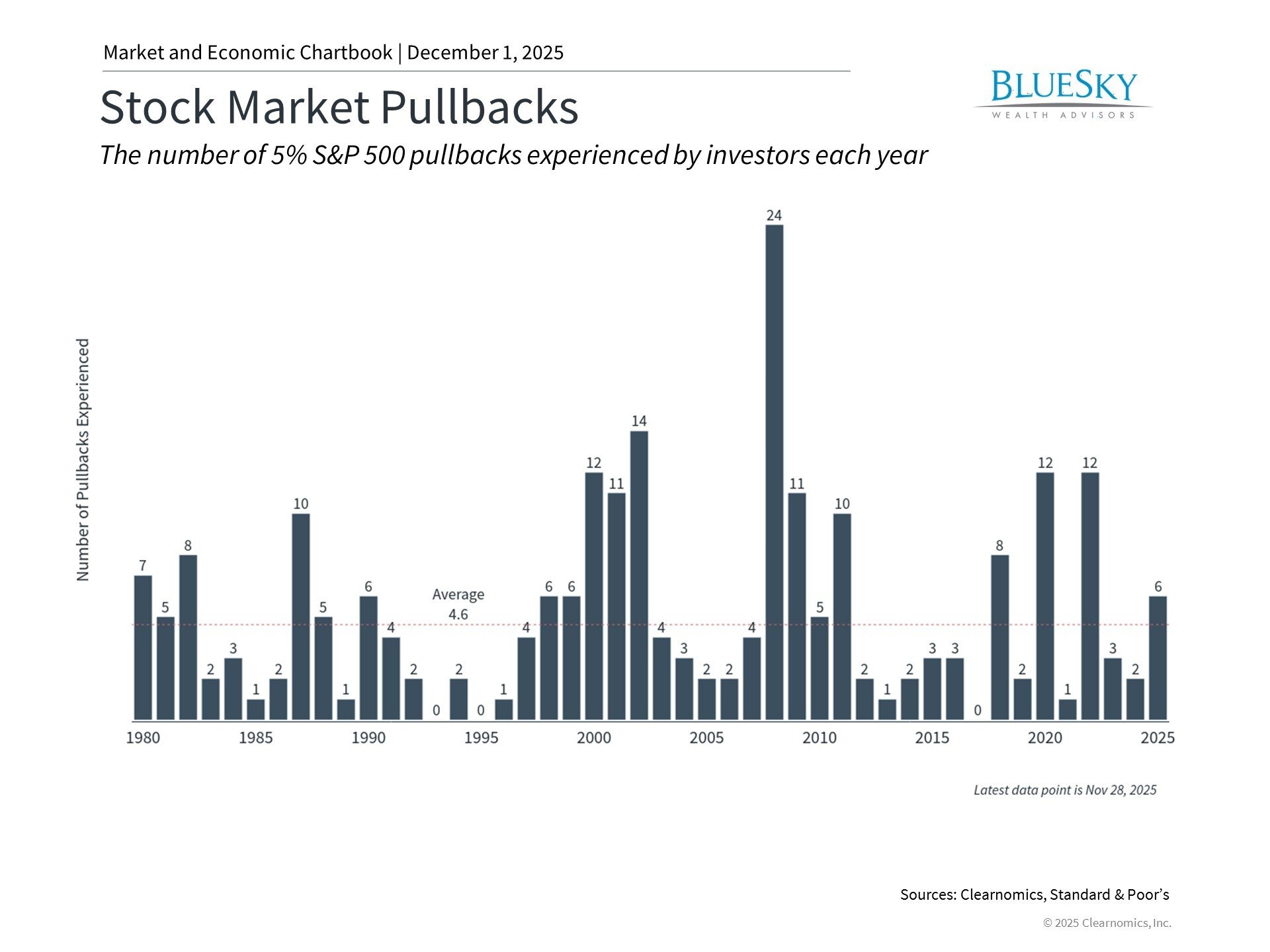

Like their bull market brethren, bears come in two varieties: (1) Secular, or long-term, and (2) Cyclical, or short-term. Interestingly, cyclical markets—bull and bear—can occur within secular markets. A word of caution, don’t confuse bear markets with corrections. Corrections may feature similar declines but they last for much shorter periods of time.

Since 1900, there have been five secular bear markets with a duration between four and 20 years plus a smattering of cyclical bears. The time between bear markets has typically been three to five years. Clearly, bear markets are a regular occurrence and investors get paid for assuming risk to get through them. But why are they a necessary evil?

NOTE: In the Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton once cautioned the citizenry about the “necessary evil” of fielding a national army. A similar analogy can be made when it comes to bear markets: They are a necessary evil* that investors must endure from time to time to earn a return.

Bear markets signal a shift away from excessive optimism (irrational exuberance) which tends to drive the market to unrealistic and unsustainable return expectations and prices. When this happens, investors are forced to reevaluate the amount of return they expect for a reasonable level of risk. So, while bear markets can be painful, they do play an important role in calculating the risk premium investors expect when buying stocks.

Risk and Expected Returns

After the global market bottom in March 2009, we experienced a few stumbles including a debt fight/downgrade and 15 to 20 percent declines in the stock market. Thankfully, these recent declines have been short and shallow. In fact, we have been in a mini-bull market for the last four years. But, when bull markets come to an end—and they will—you are likely to suffer some financial pain. That’s when knowledge of risk and expected returns come into play.

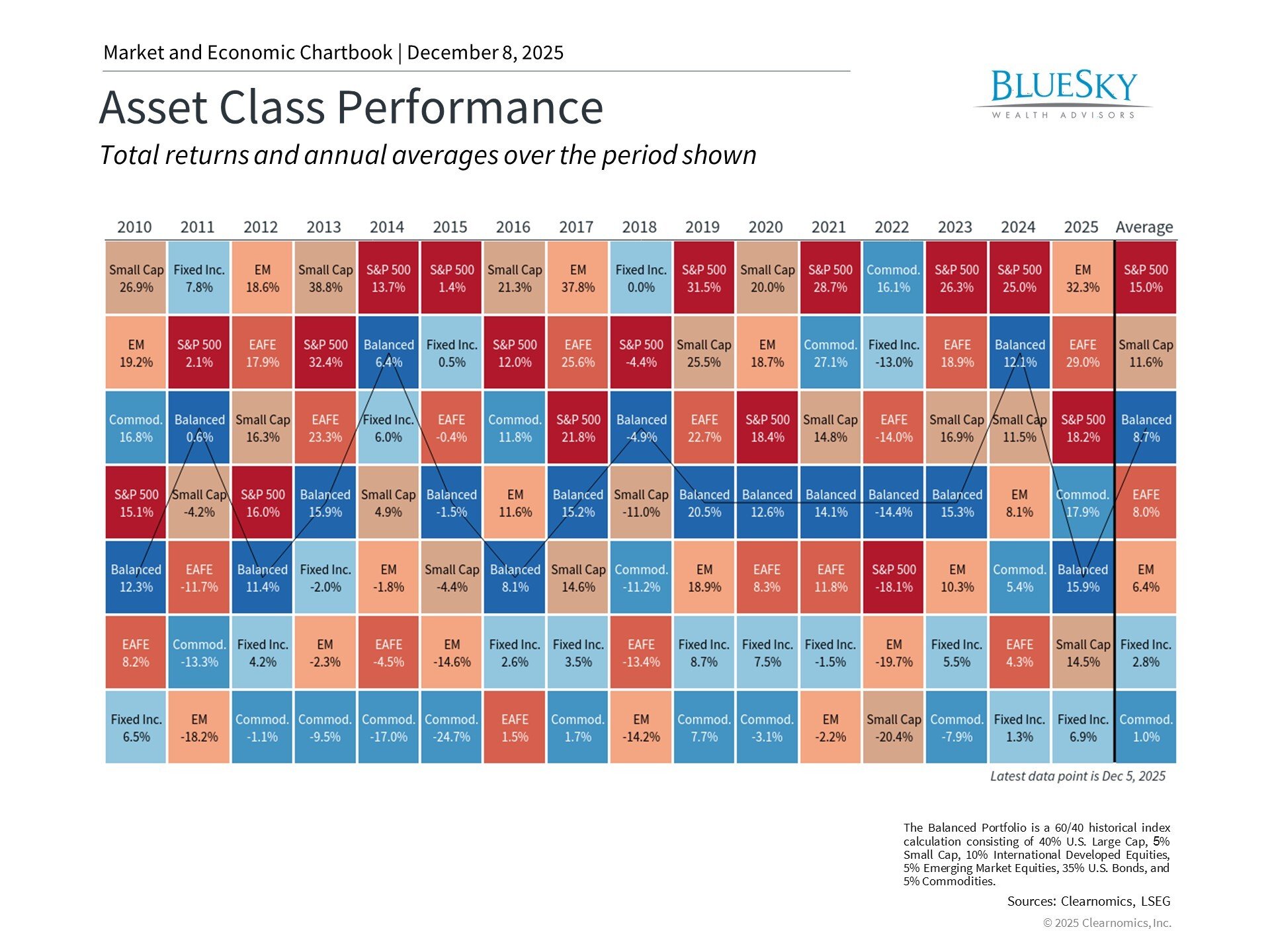

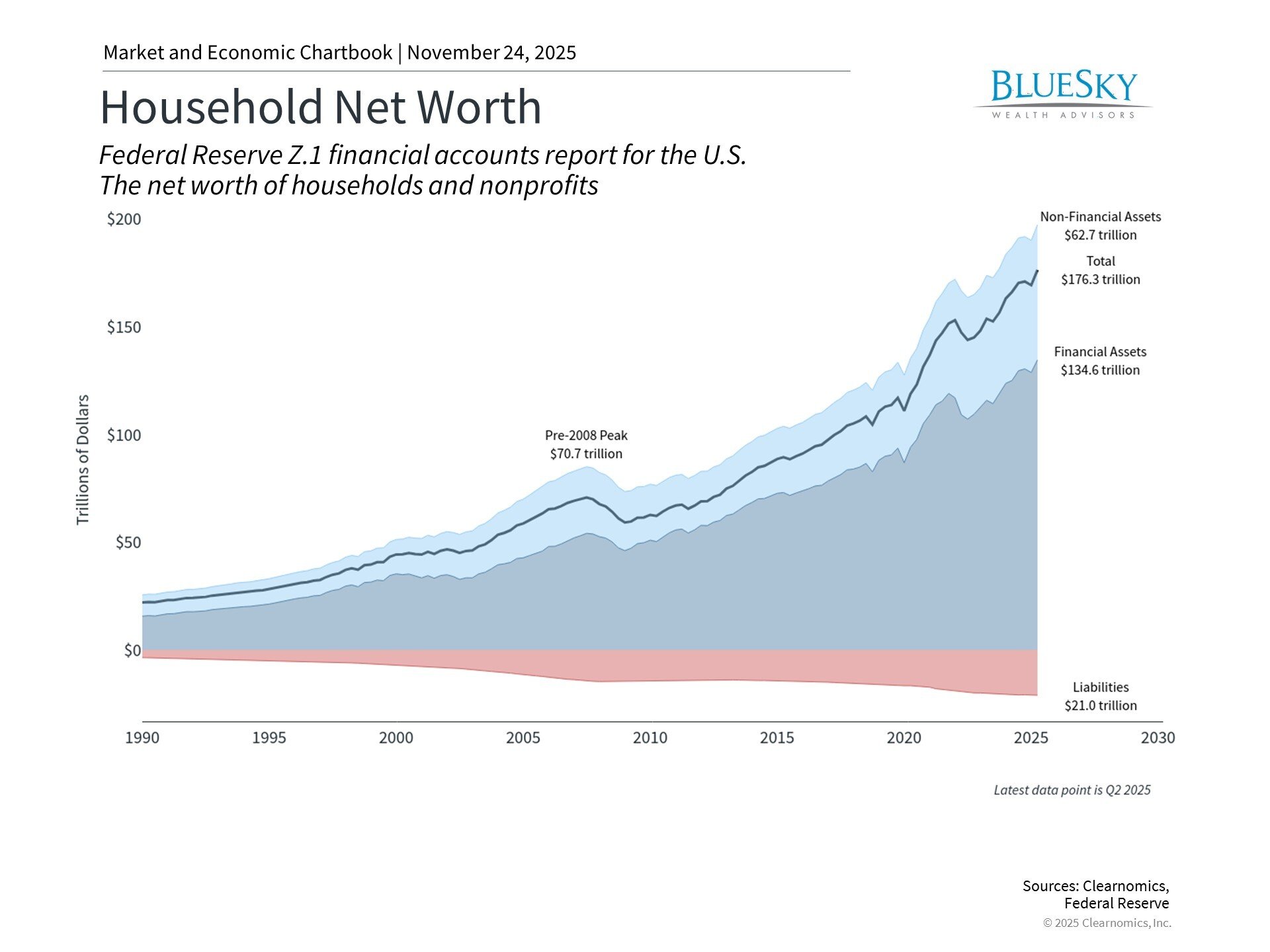

Expected returns are based on the amount of risk associated with an investment. On short-term treasury securities (the benchmark of risk-free assets) and some short-term corporate paper, returns are fairly predictable and reliable. If, however, you invest in equities, commodities or longer term bonds, returns are not guaranteed and the value will fluctuate over time. As a result, you must be willing to accept some risk in order to earn a return.

It’s important to note that if a return is guaranteed, it is likely to be very low, unrealistic or both. Think about it, if bonds always pay four percent and stocks always return nine percent, you would never invest in bonds because there is no risk in stocks. In the real world, the volatility of returns among different asset classes is what determines risk and potential reward.

This is especially true when buying individual companies. For example, in the stock market we attribute more risk to small companies than we do big companies. Not to say there isn’t risk in big companies (all of us remember Enron and WorldCom, two companies that disappeared almost overnight). But the mortality rate among small companies is pretty high, so they command more return in exchange for taking the investment risk.

Likewise, value companies (companies with low earnings multiples that are largely out of favor with investors) also offer a higher potential return and therefore more risk. This was the case in 2009 when GM was being bailed out and Ford—while not a recipient of bailout money—was experiencing declining sales and had slashed its dividend. Because there was the real chance that the auto companies could go out of business, they had to offer the potential for more return in exchange for the amount of risk associated with owning them.

On the flip-side, growth companies typically have lower potential expected returns because investors overpay for growth they assume will continue forever. But there is a finite amount of global GDP (think market share) so growth stocks can’t continue to increase in value at a sustained rate.

A good example of this is Apple. Last summer, Apple became the largest company in the world in terms of market capitalization. As we told our clients who asked about it, once a company gets to be number one, there is usually only one direction to go: Down. And, Apple has come down significantly since August of last year.

Conclusion

It’s critically important that you understand risk and reward, especially during bear markets or periods of high volatility when the discipline of investing really gets tested. If you are new to investing and didn’t experience the downturn of 2007-2009, or if you think that the Dodd-Frank bill or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau will protect you from another Lehman Brothers or AIG, think again. Putting your money under your mattress won’t eliminate the risk of someone stealing it; and putting your money in a bank won’t protect you from inflation risk. Risk is everywhere.

So the question becomes, “How do I combat volatility and survive bear markets?” First, you want to avoid panicking or worse yet abandoning ship. This happened recently when investors bailed out of Europe because they thought the euro was collapsing; Greece and Italy were going to slide into the Mediterranean, etc. But, European markets actually outperformed the U.S. last year.

The best thing you can do is set goals and devise a realistic plan based on time-tested principles to achieve them. You need to visualize what the road looks like as you invest for the future. After all, if you drive from Los Angeles to Miami, you need a road map. And while the route you choose may have unforeseen detours, you generally continue to heading east to reach south Florida. The same is true when it comes to investing.

If you believe that over time the stock market adequately compensates investors for the risk they take, you must stick with the investment plan you’ve devised. It is okay, even prudent, to make adjustments to the plan if the risk/reward ratio of various asset classes changes significantly. But you should avoid making short-term or wholesale changes in an effort to time the market.

The bottom line is, if you want to achieve your long-term investment goals, you must do three things: (1) Have a realistic plan that takes emotion out of the equation; and make adjustments as market conditions warrant or as your goals change, (2) Don’t take on more risk than you are willing to accept, and (3) Avoid getting into a market timing scheme.

If you do these things, you should find long-term success as an investor.